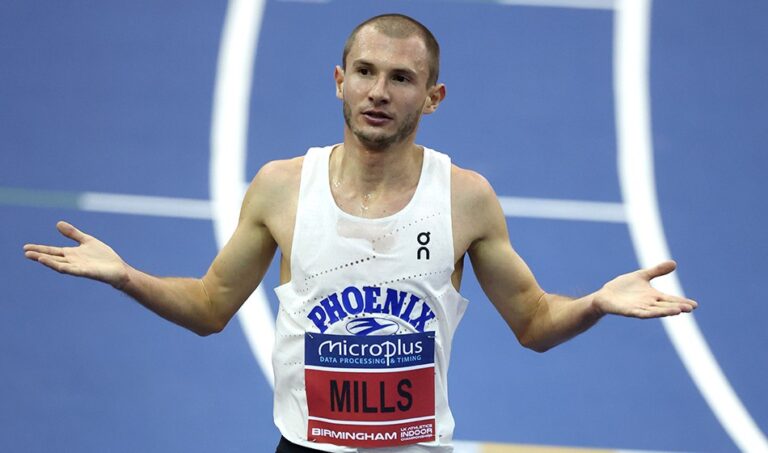

The European under-23 10,000m champion reflects on his Valencia race and the journey that has led him to become a British record-holder

Rory Leonard made history last weekend (January 12) in Valencia as he broke the British 10km record with a remarkable time of 27:38. The 23-year-old slashed six seconds off the previous mark, which was held by both Mo Farah and Emile Cairess.

Farah’s time came in the 2010 Vitality 10,000, while Cairess matched it in Valencia three years ago.

While Leonard’s victory was impressive, running through 5km in 13:45, he admits it wasn’t entirely unexpected, explaining that breaking the record had been his goal all along – despite feeling some struggles around the 3km mark.

Leonard wasn’t the only Brit with a standout run in Valencia. Charlie Wheeler finished as the second-fastest Brit and also ran quicker than the previous national record and Leonard’s training partner, Efrem Gidey, broke John Treacy’s 40-year-old Irish record by three seconds with 27:43.

Though Leonard hadn’t raced a 10km on the road since 2022, his recent performances showed him he was on the right track.

Rory Leonard

At the European Cross Country Championships in Antalya, Leonard placed ninth overall, finishing as the top Brit and winning team bronze. He also earned a spot on the British team for the European Championships in Rome last summer, running the 10,000m.

The last 10km Leonard ran on the road was when he ran 29:03 in Bordeaux in 2023. The year before that he lived in America while studying at the University of Arkansas, where both his parents honed their running.

His father Tony was a former British international, while his mother Sharon was a medallist in English Schools and National Cross Country championships. However, Leonard reflects on the move to Arkansas as something that wasn’t the right fit for his development as an athlete.

Now, Leonard trains with Team Makou, a professional group supported by Hoka and coached by Andy Hobdell. The team, which includes athletes such as Callum Elson, Scott Beattie, Ellis Cross, Efrem Gidey, and Sarah Astin, has been making waves with stellar results.

Rory Leonard (Mark Hookway)

How did it feel to run the British 10km record?

Coming across the finish line, knowing that I’d done it was pretty cool. From 5km, you’re in a little bit of panic mode because you’ve never run that fast before on the road.

I felt terrible at 3km. I was feeling pretty bad and was thinking I’ve still got 7km of this to go. I saw my 3km split and knew I had to pick it up a little bit because I wasn’t bang on pace by that point. I told myself that everything would figure itself out in a few kilometers, just sit in, stay out of the wind and tuck in, forget about everything, get to 5km, and then you’re on the way home.

I was running with [Narve Gilje] Nordas for 99% of the race – he also runs for Hoka – and I tucked in behind him and he put me away in the last 200m massively. I was pretty lucky with the group that I found myself in because Nordas was trying to break the Norwegian record, so he couldn’t let the pace drop. I was trying to break the British record, so I couldn’t let the pace drop, and so it led to quite a nice trading-off effect.

In the last 50 meters where I could see the time properly, I knew that I was going to get it, provided no Brit came around my shoulder and beat me.

Did you know you were capable of breaking it?

That was the reason why I went, I didn’t go for any other reason. But I also think that there were three or four guys who on their best day, could have done it. There are a lot of people who can do it, but it’s just about getting it done.

There are so many factors of whether you do it or you don’t do it and it’s getting it right on the day. I told people beforehand, that you could be someone who breaks the British record in this race and be the third Brit across the line if everyone has a good day.

For me, it was if you go out fast enough, go hard enough, then the time will be there at the end.

What did you make of the strong performance from the other Brits?

It says so much about the depth that we’ve got in the UK at the moment in the distance scene, which is great news. I mean, I’m very happy that Charlie [Wheeler] was four seconds behind, I didn’t know he was coming, but he was.

Charlie and I were at Loughborough together in 2020 and at the time we were like 14-minute 5km guys. We weren’t anywhere near the top at that point, we were sort of plugging the miles away together. So, it was pretty cool that we came across the line close together. Obviously, he broke that previous record too so it was pretty nice to do that with Charlie.

What does it mean to take the British record from athletes like Mo Farah and Emile Cairess?

It’s a tricky one with Mo because I’m sure that if he had really given a 10km road race a go when he was in his prime, he would have run a lot quicker than 27.44. It’s cool that he didn’t because I get to say that I’ve broken his record. But I also acknowledge that he’s a different beast and, a double Olympic champion.

On the Emile front, I look at him now and the way that he’s done things. I do look up to him and I think eventually I’d like to be as successful as he is. I think that’s down to his hard work too. So I’d like to think that I’m on that trajectory for those future championships and stuff.

What does training look like in the build-up to this?

I haven’t done a 10km on the road for quite a long time. We did the San Silvestre in Madrid last year, well in 2023 on New Year’s Eve, which is 8km directly downhill, and then a 2 hard km jump. It’s just chaos.

Training-wise, I came ninth at European Cross in mid-December and knew that I was in a pretty good spot. We didn’t change much in the build-up to this, it was very steady, the usual weekly schedule that we would do just with a little bit of tune-up work. But nothing crazy. It was just enough that I could use my fitness and tune up a little bit to go through 5km comfortably.

Rory Leonard (British Athletics)

How did your coach and team react to the record?

Andy was buzzing and of course, Efrem got his Irish national record, too so we came across the line at the same time, found Andy and it was nuts. We couldn’t have done better on the day for the group, especially for me and Efrem.

We all knew it was going to happen so more than anything, it was validating that that’s where we’re at. It was such a good feeling that what we’re doing is working and we’ve got a great atmosphere around the team.

We’ve got a great group. Everyone’s willing each other on and then when you get performances like that, it just shows everyone that everyone else in the group is going to have these breakthrough performances as well.

Why does your training group work so well together?

I imagine that, with other groups, the brand pulls people in who potentially don’t know each other. What we had was a group of five friends who conveniently were trying to turn pro at a similar time. We also had a very like-minded person in Chris Rainsford at Hoka who wanted to pull this team together and without Chris it wouldn’t have happened. It came together so naturally that we didn’t rush it.

We didn’t announce the team until July of this year and we’d been going about six or seven months before that. What we have is a genuine friendship, it is a friendship group and I think that it’s different to other teams where they’re signing athletes.

They want the groups to work together and there’s no guarantee of chemistry. But what we had was chemistry before it was a pro group and I think that’s what’s special about our group.

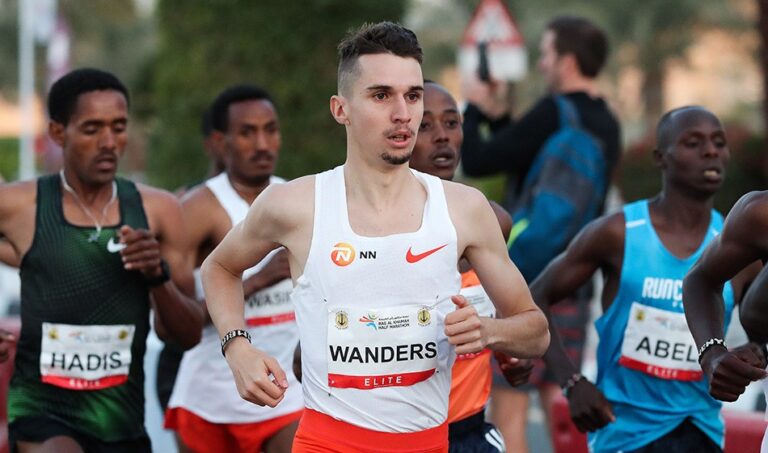

Andy Hobdell (Charlie McCarthy)

What has your transitional journey been like from a youngster to now?

It’s strange because I haven’t missed a GB vest every year since I was 17 and I’m 23 now. But every single one of those years has looked so different. It looks great making GB vests, but I’ve had years where things were going great and things were going terribly.

I’ve managed to get here by learning from huge mistakes in the build-up and one of those was going to America and figuring out that it’s not the right fit for me. But luckily I had the fitness to come back to Liverpool and make a team.

In terms of transitioning to the seniors, I think I’ve always been told by my dad, who was a great runner as well that the under-23 age group exists and it’s nice and helpful to transition through. If you come out of that age group right, then you’ll be one of the seniors at the front and you’ll be doing what you’re doing.

I think I’ve bumped up nicely every year, training-wise, quality-wise, volume-wise and it takes that as well to not get injured. I know some people get unlucky with injuries.

How does your dad’s success in running help you with your career?

He also went through the highs and lows of his career. He understands what it means to break a British record or to get anywhere near that, and to achieve something like that. So for him, I think it’s also pretty surreal.

I think in his mind, I’m his son, right? He always thought I would do something like this. So that’s lovely but I think doing it is pretty special. To have a family who completely understands it and the work that’s gone into it, it’s great.

What are your goals for 2025?

I’m not entirely sure, because I would love to make the world champs, right? But the time is 27 flat to get into that championships. The ranking points are going to be hard to come by so my absolute, almost unrealistic, goal would be to make that world championships.

I’m going to go to Sound 10km [The Ten] on March 29 and that’s when I’ll take a big swing at getting the potential UKA standard and seeing if that’ll bump me into the rankings. But apart from that, I think it’s a bit of a free hit of the year.

I’m going to go to Boston next month, to try and run a fast 5000m. My PB at the moment is 13:29 and I can run a lot faster than that and ideally, I’ll do that next month.

I think with these times being set at something like 27 flat, you’re not going to do it in a year. I’m quite lucky in the position that I’m at with the funding, being able to be full-time with Hoka, and I can see myself getting there, but it might take a couple of years. It might take a few years to run 27 flat. You’ve got to do an awful lot of training and you can’t cram all that into one training block.