The former UK Athletics Director of Coaching talks about his philosophy, the role of the coach and why people skills are becoming a key tool

Coaching conversations with Frank Dick

There are few people who could match Frank Dick’s depth of involvement in coaching.

The former national coach in Scotland, from 1979 to 1994 he was the British Athletics Federation’s Director of Coaching, as well as personal coach to two-time Olympic decathlon champion Daley Thompson.

A motivational sport, business and performance speaker, Dick has also worked across a range of sports and organisations, and currently serves as Chair of the Global Athletics Coaches Academy, created on behalf of World Athletics.

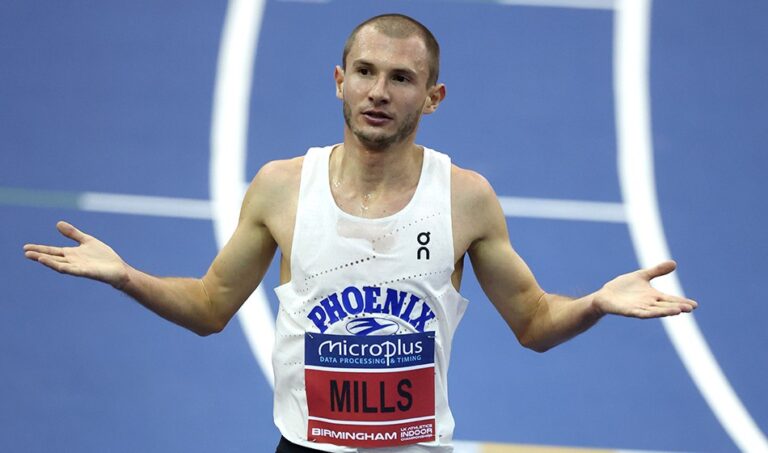

Kriss Akabusi and Frank Dick (Mark Shearman)

How did your coaching journey start?

I went to Royal High School in Edinburgh and ran the under-16s half-mile at one school championships, finishing third. I really thought I could do something in athletics. I got selected for the school team for a competition that was coming up against George Watson’s school. I think I finished first in that race and that sold me. I persuaded my mum and dad to pay to let me go to the Scottish Schoolboys course and I can still remember this giant of a guy called Tony Chapman, who was the Scottish national coach.

I worshipped him because he was coming out with so much wisdom that no other person in the world had ever spoken like this before. And at the back of my mind, probably then, I wanted to be a coach.

I had a passion for athletics but I developed an even deeper passion for understanding more about it and for passing that on.

How do you view the role of the coach?

I think a coach’s function is to create a learning environment. But for what reason? It’s to create a process for the athlete to take ownership of their development and of their performance. If we broaden it further, taking the holistic side, that doesn’t apply to just helping you to perform better in the arena, but to perform better in life.

I really embraced [American basketball coach] John Wooden’s concept of what a coach’s job is when he said it’s to take people from who they are to who they’re capable of becoming.

How would you sum up your coaching philosophy?

We are brought up with a fantastic basic philosophy in athletics, and it’s around a concept called personal bests. This sums it up – be better today than you were yesterday, every day. And that applies not just to a junior athlete just starting out but it applies to Usain Bolt. Otherwise, why did he go from Beijing one year to Berlin the next year and destroy his world records again? You could say: “Well, there’s money in it,” but it’s more than that.

It’s like [American football coach] Bill Walsh said in his book: “Take care of performance and the score takes care of itself”. To me, that’s absolutely the case.

It doesn’t matter who you are when you go into that arena. If you don’t deliver the performance, you’re not going to get the result. So stop looking at the result.

Don’t look at the scoreboard, look at your performance and stay in the moment. Whether that’s in training or whether it’s in the arena, it’s both the same thing.

I was also absolutely obsessive that I didn’t know enough. There was always something more to learn.

I worked quite often with Alex Ferguson and he said the two most important things you have to do as a leader or as a coach are to help your people to deal with failure or success. My mum used to say success breeds success but Alex said success can derail progress – you must never be complacent.

In my mind, you never arrive and you never arrive in your learning. I believe that any winning culture must be founded on a learning culture.

Sir Alex Ferguson (Getty)

What advice would you have for someone just starting out on their coaching journey? Would it be to keep that open mind and to keep learning?

I think that’s the energy that must be behind everything but what I would also say is there are only three things you have to know in life. First, you’ve got to know what you know – really know it. Secondly, you’ve got to know what you don’t know, or at least admit it. Thirdly, you’ve got to know somebody who does, and bring them to the party.

We’ve each got our limitations but you must never make your athletes the victim of those limitations. Make sure you’ve got either a network or at least one person that you respect and who’s been there before to bounce your ideas off and to share your experience with, so that you actually do learn the lessons of experience, or you’ll miss them.

And what about a coach, perhaps at the grassroots level, who has been doing this for a while and is feeling stale, in need of new inspiration?

Be curious and keep an open mind. You’ve got to be willing to ask the questions. I’ve got two daughters and when they were tiny, I used to say to both of them: “You know, asking a question is not the sign of stupidity, it’s a sign of intelligence.”

Keep asking the questions until you get answers. Life changes around us all the time so don’t have a mindset that goes into a conversation that’s saying, what’s the solution? What’s the answer? Always go in with a mindset that is, how many solutions are there? How many answers are there?

Are there any mistakes you see being made when it comes to coach development?

I think one of the things that maybe has been missing in a lot of coach education programmes in the past has been, not the technical stuff, it’s the people stuff that we’ve got to look at far more. Do we really take time to know our people?

Do we really make time to know their stress signatures? Do we take time to work out: ‘Am I getting my language right?’ Because not everybody hears the same thing from the same word and I think all of that conflict resolution, how to deal with leadership, how to deal with being a member of a team, these things we don’t often talk about when it comes to coach education. But I think that’s paramount.

We’ve also got to be careful that being focused is not the same thing as being blinkered. You can be focused, but you’ve got to be able to scan all the time. What are the things out there that could influence what I’m trying to do and what I’m trying to achieve in coaching personally and for the person I’m coaching? I think we’ve got to get smarter at that and, again, that’s a people skill.

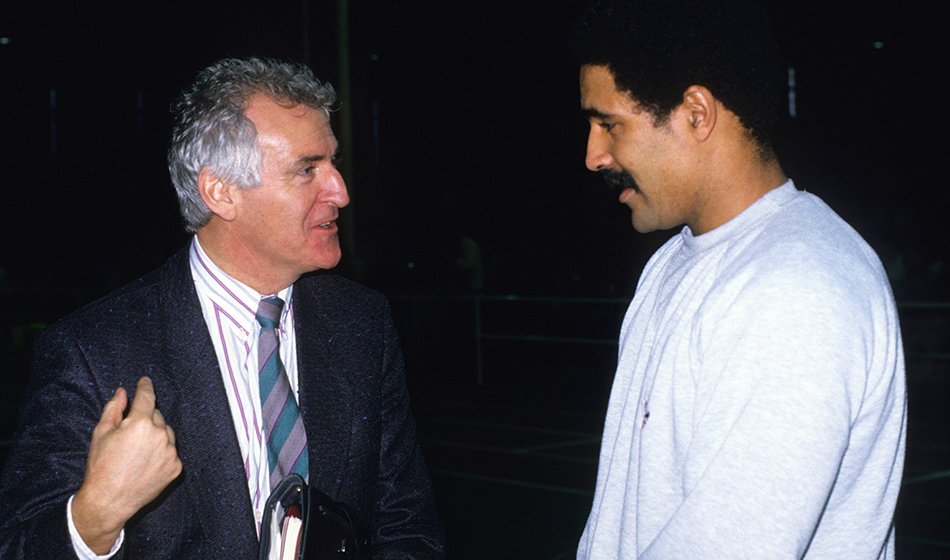

Frank Dick and Denise Lewis (Getty)

Are there lessons we can learn from the past?

After Britain had a very bad Olympics in 1976, winning only one bronze medal through Brendan Foster, there was a serious examination of where we were at that point.

I was Scottish national coach at the time and I was asked to design a coach education programme so I did and I tried it out in Scotland. When I became the director of the British federation, I asked Carl Johnson if he could take that on.

A lot of people looked at Britain as having the best coach education programme for track and field. The record shows what happened when I was the head coach and an extraordinarily gifted generation of athletes were coming through. But, more importantly, there were also an extraordinarily gifted generation of coaches.

Before we went into the Moscow Olympics, we had a difficult selection situation because we had five of the top 10 in the men’s 1500m in the world – and each one of them was coached by a different coach. How good is that? One of the things that I didn’t like about the notion of a centralised institute or place where everybody who was good came to is that it not only disenfranchised local coaches, but also it kills competition and competition is the essence of progress.

In the more recent world, if there’s a good coach, athletes will gravitate towards that coach and I get that. But there has to be a bigger mind that steps back from all of that and says: “Is this good for our future? Will this give us sustainable achievement?” Because that’s what you want – not just a one-off flash in the pan.

How did you bring people with you?

Go for the coaches, not for the athletes. Work with the coaches and try to discuss with them, understand their philosophies, add to that if possible, and try to enrich that process. In terms of the egos out there, some of them were easily managed, some of them weren’t. But one thing that did occur to me then, and I believe is also true in the current world is that we do not intuitively think like team players in athletics.

The fact is, if we don’t work together, we die. We simply must learn how to work together.

I stole a word from a book – coopetition. I use this at World Athletics level when we’re trying to create a new mood for coaching worldwide.

We’re in it to compete but unless you co-operate and work together, coaching will never grow. There’s the development of coaches and the development of coaching that we must think about. We’ll only achieve that if we work together, if we think together, if we co-operate.

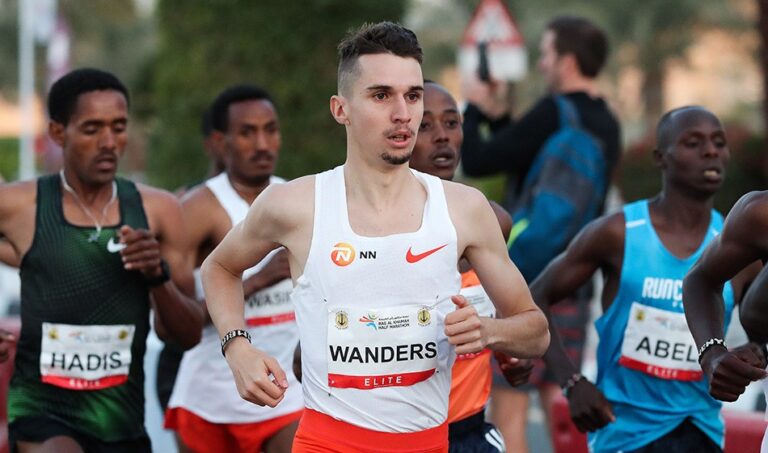

Seb Coe (Getty)

Is there enough value placed on coaching?

When the Global Athletics Coaches Academy was formed, it was done so at the request of Seb Coe. He wanted a body to be formed from the coaching community to deal with athletics coaching related matters and to facilitate necessary change.

We’ve done good things but the issue remains that the public perception is not particularly strong about the position of coaches and coaching. We are working very closely with World Athletics to create a different perception of the culture that will correct this going forward.

At the end of the day, we all love the same sport and we love what it stands for.

Nobody’s got the right to say that they understand it more than anybody else. We all have our own understandings of it.

What are we in this for? If it’s not working, find a way to make it work. And for the most part, it will not be a technical thing, it will be a people thing. It’ll be about behaviours and it’ll be about relationships.

PHOEBE GILL SETS STUNNING EUROPEAN U18 800M RECORD